Introduction

Back in the 2000s, I sort-of quit my day job and went to University to get a BA degree in Graphic Design. I learned a lot (mainly that I should have gone somewhere else and studied illustration, but never mind). I did get the opportunity to spend many weeks working on a comic book, something I’d wanted to do for a long, long time.

This post is (more or less), the essay I turned in to accompany my degree project, a Short Stories for Modern Times. It’s available as a PDF to download.

Preface

For reasons having much to do with usage and subject matter, Sequential Art has been generally ignored as a form worthy of scholarly discussion — Will Eisner[1].

In the 20-odd years since Will Eisner wrote the above words, sequential art (also known as ‘graphic fiction’) has grown far beyond the common perception of a world populated only by super-heroic men in tights. Sequential art is a storytelling medium, a unique combination of text and images that blends elements of film-making with literature through graphic design. This art form has not only become the subject of much scholarly analysis[2] –in a large part due to Eisner’s own ground-breaking graphic novel, A Contract with God 3 – it is also a highly profitable industry, reaching some $330 million in market sales in North America alone in 2005[4].

In this essay, I take a phenomenological approach[5] toward sequential art as the basis on which my interest in drawing, typography and writing can be combined into a career.

Early influences

As a child, I read voraciously and knew instinctively that I would make my career as a writer. Reading was an addiction. There was no differentiation: fiction, encyclopedias, my mother’s magazines like The Ladies Home Journal and McCalls, billboards, the newspaper. Anything and everything readable was read. Libraries were the main source to feed my habit, but cheap and affordable comic books from the second-hand bookshop were also a mainstay. Early reading focused on the DC Comics heroes such as Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster’s Superman[6], Bob Kane’s Batman, and the multi-character Legion of Super-Heroes (my favourite was Saturn Girl with her red and white costume, yellow go-go boots and telepathic powers). The cheerful teenage mishaps and adventures of the Riverdale set (Archie, Jughead, Betty and Veronica) also appealed. This was despite their animated incarnation’s infliction on us of the pop song “Sugar Sugar”. As I grew older, these simplistic characters gradually lost their attraction. DC’s competition, Marvel Comics, with intricate plots and Jack Kirby’s new and originally different artwork became my comics of choice. These included Stan Lee’s angst-laden Amazing Spiderman, the mysterious sorcerer Dr Strange and those ultimate mutant-teenagers-in-turmoil, The X-Men.

At the same time, ‘real’ literature – some with wonderful illustrations – was also being absorbed by my younger self. Illustrations that made an impression included the sensitive line drawings by Pauline Baynes[7] in C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia[8]; N. M. Bodecker’s pouty-lipped children in Edward Eager’s Half Magic series[9]; Louis Darling’s 1940s-style sketches in Beverly Cleary’s Henry Higgins and Ramona books[10]; and Mary Shepard’s highly non-Disney illustrations of Edwardian London in P. L. Travers’ Mary Poppins series[11]. However, of all the many, many books I read, the most memorable illustrations were in the precious, large-format antique L. Frank Baum books. The books had belonged to my best friend’s grandmother and were full of whimsical and sinuous art nouveau drawings by John R. Neill[12], the “Royal Illustrator of Oz”*.

Another important influence from this time was J. R. R. Tolkien. Surprisingly, it was not so much the story-telling as his handwriting: it was the appendices in the Lord of the Rings[13] that inspired me to take up calligraphy and contributed to a love of letterforms that would eventually lead to typography.

The last influence from those early days was not so much pursued as inhaled along with humid, tropical air. I grew up in Miami with its languid, chameleon-like anoles, palm trees, hurricanes, Cuban refugees (and a certain famous missile crisis). But like Davy Crockett, I was born on a mountain in Tennessee, the straight-laced buckle on the Bible Belt that strangles the deep, rural South. My parents grew up on adjoining farms; electricity didn’t arrive there until the 1940s. My mother was religious, frugal and resourceful. She made quilts from our worn-out clothes, she taught me to crochet and sew. There was no ‘art’ as such in our home, but there was a strong tradition of home-spun craft.

Current influences

After a long absence on my part from sequential art, Neil Gaiman’s work (particularly The Sandman[14], more on this later) helped bring me back into the world of comics. So, it was gratifying to read the following on his Journal[15]:

When I decided I wanted to write comics in 1985 I went out and bought Will Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art. If I were doing it now I’d also buy Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. —Neil Gaiman

Will Eisner’s book, quoted earlier, along with How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way [16] have lingered on my bookshelf since the 1980s. McCloud’s Understanding Comics and its sequel, Making Comics [17] are new but well-thumbed. McCloud articulates, with humour and clarity, the familiar language of comics and explains the logic underlying the basic concepts, e.g., what happens between panels on a page. Even before reading Gaiman’s advice, I had consciously chosen to use McCloud and Eisner as my main guidance in creating sequential art.

A few years ago I began investigating how some ‘traditional’ comics (or what I thought would be traditional) to learn how comics have changed over the years. I went back to familiar characters from my childhood, starting with Frank Miller’s take on the Batman [18]. This modern version was a rather startling experience: it was most definitely not the Gotham City of the 1960s. It was dark and gritty with unemployment, cruelty, homeless people and murder. From there, I moved on to modern graphic novels such as Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and then to The Sandman.

The Sandman was unlike any other graphic novel I’d ever seen. If the covers were surreal (strange fine art collages with floating haunted faces), the body text was equally new. Other graphic novels – despite taking on modern, adult themes – still tended to rely on traditional 1960s comic book typography and iconography – all sans-serif capitals with bold italic for emphasis; oval speech bubbles and thought clouds. The Sandman turned that ‘traditional’ typography on its head, first of all by using mixed case. Secondly, the recurring characters, known as ‘the Endless’ are as recognisable by the unique treatment of speech as by their clothes and faces. The speech of the title character, known as “Dream”, is jagged, white on black text as gothic as his clothing. His siblings: Destruction, Death, Despair etc. all have their own typefaces and speech style, e.g., Delirium has a psychedelic rainbow persona with text to match. This technique is also used in manga, e.g., in the romance/vampire horror series Model by Lee So-Young[19].

Alongside the Western collections, manga has been one of my other main sources of inspiration. Manga (which means ‘whimsical drawings’ in Japanese) covers many genres and has a wide following, not only in Japan and North America but also in France, Germany and the UK†, [20], [21]. McCloud[22] says manga’s popularity is due to the way its unique graphic techniques add up to a heightened sense of reader participation – a sense of belonging in the action, rather than simply observing it. It also caters for a much wider audience than the Western bunch of spotty adolescent boys (and the occasional geeky girl).

Current practice and theory — iconography

As a child it was immensely frustrating to be unable to produce drawings that resembled the work of the illustrators I admired. This was apparently due to what Betty Edwards[23] calls the left brain’s symbol system, a process of rendering real-life objects as icons which supports our acquisition of written language. Children know, for example, that a chair has four legs of equal length, a seat and a back. When asked to draw one, they cannot easily suppress that knowledge to draw the chair accurately. So, their drawing of a chair will have four legs of equal length even when viewed at an angle where foreshortening and perspective requires the closest chair leg to appear longer and larger than the others. As a teenager, learning to suppress that symbol system and draw realistically was a triumph.

So now, taking a decision to work as a sequential artist is ironic on more than one level. Firstly, it requires me to make a strong investment in learning a new language of symbolism and iconography that differs for manga and Western-style comics (although there is some overlap). Secondly, the naturalistic style I so desperately desired as a child is not necessarily the most appropriate for this relatively-new art form. Simplicity in rendering the characters, as McCloud[24] points out, is vital for enabling the audience to identify with them (more about characterisation below).

McCloud also tells us that the iconography of sequential art extends beyond the use of a few familiar symbols and it rapidly builds up into a completely new vocabulary. These start off with things like a fairly realistically-drawn light bulb to signify a bright idea; or the convention of using a scalloped cloud and ‘bubbles’ to represent unspoken thoughts. The symbols can become increasingly abstract yet remain instantly recognisable: a few wavy lines can indicate smoke, yet the addition of a few strokes (a small dot with two loops and a c-shaped line behind it) means the wavy lines have attracted a fly, and that probably adds up to a bad smell. There are Japanese symbols that are unfamiliar to non-manga fans, such as a ‘snot bubble’ coming from the nose that represents sleep, replacing the ZZZZs common in Western comics and cartoons.

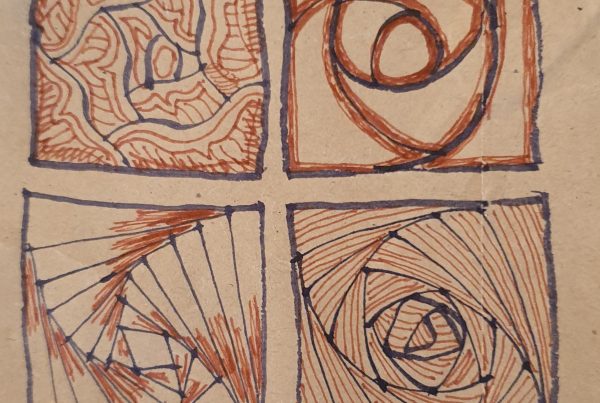

In both Western comics and manga, ‘action’ lines are used to indicate speed, direction and the force of blows in a fight. In manga, however, a male character’s inner turmoil can also be represented by similar action lines. Emotional content in shouju‡ manga has its own special iconography: feathers and sparkles replace little hearts to indicate true love[25].

In addition to the overt symbolism which must be learnt and which can be very different between manga and Western comics, there is also the challenge of harnessing the implied emotional content that is built up from the varying line weight, changing the size and shape of the panels (indeed, if there are any panels at all) and the use of colour and so on. Shouju tends toward light, playful line weights, shonen is heavier and more dynamic.

Page layouts and panels

A major aspect of creating sequential art, and one that has no parallel in other art forms, is the role of panels which are essential to create the illusion of the passage of time.

How many panels are used – whether to use them or not – the size and the shape, all strongly affect the emotional content of a page, its legibility, and control the pace and flow of the story itself. Eisner, for example, advocates incorporating background elements as panel borders to convey a sense of place (or claustrophobia)[26].

Manga stories tend to be told in a serial form, with stories running to hundreds, if not thousands, of pages. It is not uncommon for a whole page to be devoted to a depiction of a sunrise and the way the light moves across the face of a building during that time. Western comics, as McCloud says, are more goal-focused and tend to wrap up a story in 8, 16 or 24 pages. Even The Sandman, which ran over ten collected volumes and perhaps 2,000 pages, was composed of many short stories while the underlying long-term history of Dream and his siblings, (‘the Endless’) only gradually revealed itself.

There is another school of thought that says a standard grid of panels can create a sense of structure and authority. This was especially prevalent in heavily illustrated and complex story that can evoke a sense of the 1940s and ’50s. Watchmen used a nine-panel-per-page layout as the standard for those reasons[27], but in some ways that seems to me like a coward’s way out. Easy, but unimaginative.

Applying the concepts to my own work

I believe characters and plot are the two most important aspects of sequential art. Revealing the plot is controlled by the page layout. I’m not there yet, but I believe that if I can get these two elements working well together, the rest will (presumably) fall into place.

Characterisation

In manga, most protagonists have simple, sweetly childlike and beautiful faces but the villains have warts, wrinkles and harshly drawn features. McCloud’s view is that this distinction allows the reader to identify strongly with the heroes while maintaining a sense of ‘otherness’ that separates the reader from the bad guys. In the European comics tradition, Hergé was a master of the technique, keeping the much-loved Tintin’s features simple and boy-like against strongly realistic backgrounds. Similarly, Art Spiegleman’s Maus uses very simple visual characterisation (mice vs cats) to tell an emotionally harrowing story set in the concentration camps of World War II.

My personal style of drawing characters has been based on these concepts. Despite the popularity of the manga style, I try to keep the faces as simple as possible whilst maintaining a more individualistic look for each character than is common in manga. I find the over-simplification of facial features in serious manga to be slightly confusing in terms of following the story. This becomes especially obvious given manga’s propensity to revert to a near ‘stick figure’ style of facial features in moments of joy or extreme emotion. Similarly, I believe the genderless androgyny of some manga-style faces distracts from the story. While my style is far from the big-breasted, curvy Amazons drawn ‘the Marvel way’, I want my readers to be able to tell the boys from the girls.

Telling the story through panels and page design

My current working method for getting the story out of my head and onto the paper looks (from the outside) like a car with a drunk at the wheel, veering between lanes. This is neither a wholly visual art form nor a yet a written one. Having spent 20 years writing technical manuals, my first instinct is to try and write a script. But it is a visual art, so I also draw thumbnails (if it helps Neil Gaiman[28], who is not an artist, then it ought to work for me). Usually a story starts in my head as a single image. For example, in the Cold War comic it was the floor-level view of Barbie’s high heels and seamed stockings queuing in a cold, empty Moscow shop with big Russian women wearing sensible shoes and heavy overcoats. I drew that single image as a tiny, single panel, and then gradually added many more tiny panels. Later, I re-assemble all the one-off panels into rough page layouts, with a lot of shuffling to get the right balance.

There does not seem to be a formula for getting the panels and page layouts right, although a bad layout jumps out immediately when I see one. A bad layout hides important details. If it makes me have to go back and look at it again to find out what just happened, I consider that a failure. Just getting on with it and drawing hundreds of pages will help me get it right.

Artwork

Up to now, I haven’t said anything about the art itself or drawing styles. Every possible variation of drawing style is seen, from carved wood effects to photorealism and pop-art§. Dave McKean may have started the trend for fine art in comics in the covers for The Sandman, but basically, now, anything goes.

The Sandman in particular has inspired me to move away from the bright, flat colours of the ‘traditional’ superhero-styling of my childhood and to try new techniques, notably watercolours and screen prints. I’m still working towards a style of my own, but it definitely will not be too realistic. I’m not actually sure that it’s possible to challenge traditional design barriers any more (nor that I would want to). But, almost without realising it, working in printmaking has served to loosen me up and my future work will almost certainly include crochet, other textiles and found objects.

My most important challenge in learning to make the most of this art form is to stop compartmentalising different aspects of art and work that I do. For example, celtic patterns and art nouveau (from the memory of Neill’s Oz illustrations) have a strong influence on my craft work. Synthesising those and other aspects of my craft work and drawings into a coherent (and marketable) style that will not become boring, either to me or my readers, is my goal.

Plotting and “my personal vision”

The final challenge for me is the question of how to acquire plots. Although writing per se is not hard for me, I find it more difficult to generate a believable and suspenseful plot. I tend to rely on history or folk tales but a fellow student has suggested that I use stories from my own life**. Comics, being that strange hybrid of art and words, lend themselves to personal storytelling; perhaps for the same reasons that self-portraits are so prevalent: you don’t have to pay a model to do one. Ivan Brunetti believes the personalised nature of comics goes deeper than mere plotting and is essential to the art itself:

The cartoonist creates – one might also say discovers – these sequences, a process of communicating how he or she sees the internal and external world, the passage and interconnectedness of time. Cartooning is a “transmittal of thought and soul” … through doodles.[29] — Ivan Brunetti

I’ve no doubt that happens, perhaps subconsciously, on an artistic level. Should I choose to take that approach literally (i.e., make use of episodes from my own life), I would be in good company: Robert Crumb, Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes use their own lives as subject matter. Even Charles Schulz supposedly based Charlie Brown on himself. Clowes said, (talking about the character ‘Enid’ from Ghostworld):

When I started out I thought of her as this id creature – totally outgoing, follows her impulses. Then I realized halfway through that she was just more vocal than I was, but she has the same kind of confusion, self-doubts and identity issues that I still have – even though she’s 18 and I’m 39! [30]

I’m not sure that my current, rather mundane middle-class existence can be converted into something as meaningful or thought-provoking as Ghostworld, although the survival struggles of a middle-aged superheroine called ‘Whingewoman, Mistress of the Rant’ is certainly within my gift.††

Personalising a comic would also be a good mechanism for not losing momentum. Chris Ware keeps a graphic diary so obsessively that he won’t go to sleep until he draws his daily entry, even after a long day working on comics[31]. A graphic diary is probably a good place to start, and I can see where it goes from there‡‡.

And finally

In pursuit of manga, several years ago I attended some workshops run by Sweatdrop Studios[32], an enthusiastic collective of young, part-time UK manga artists. They work mostly in the ‘shoujo’ (cute girly) style and have a modest following of pre-teen fans. It was a useful, although moderately discouraging experience. None of them were making a living at it, although they were approaching it professionally and one had even recently published a useful book on digital illustration and production covering the various manga styles[33]. An analysis of five or six of their books showed it to be clear that, although passion and talent were abundant, their basic storytelling skills (pace, plotting etc.) were lacking. It was a useful lesson in basic error avoidance; it’s not enough to draw well, getting the entire package right is essential for success.

Later, a visit to a Comic Expo in Bristol and interviews with a comic shop owner in Aldershot[34] brought home the need to establish my target market, apply that knowledge to marketing (perhaps through Miss Austen?), prove that I’m in it for the long term, and, most importantly, not to give up the day job just yet. It may be a growth market, but the independent comic producers do it for the love of the craft. Only the comic shop owner squeezes a living out of it and he doesn’t take holidays. However, I’m pleased to report that Sweatdrop Studios are doing well, so there may be hope for me yet.

Despite the intense competition, everyone to whom I showed my comic book was helpful and kind. The comics world is actually quite a small community, but it seems to be populated by interesting (and poor-but-nice) people.

Time to get out my trusty sonic screwdriver, sharpen Miss Austen’s quill and start work on the five-year plan…

References

REFERENCES

* Do not confuse the literary world of Oz with the 1939 Judy Garland film; the two bear no resemblance to each other. The much later film sequel, Walter Murch’s Return to Oz (1985) with Fairuza Balk as Dorothy was a compilation of several Oz books and was far more faithful to the original illustrations.

† Estimated scale of German manga market to be from 50 million Euros (7.5 billion yen) to 70 million Euros (10.5 billion yen). Estimated scale of French manga market to be at 87.5 million Euros (13.1 billion yen). Source: JETRO, Japanese External Trade Organization.

‡ Or shoju, meaning “girl’s themes”. Shonen manga describes “boy’s themes”.

§ Which came first, pop-art or comics? One can argue that comics are a form of

pop-art themselves.

** Apparently my life is interesting. One young colleague at a former job said, “You’re so full of surprises. You seem like a nice, ordinary older lady, but then you casually mention something like selling airplane parts in Miami, and you’re always doing that. How many different jobs have you had, anyway?”

†† Hmm. Not a bad idea… she marshalls the powerful forces of graphic design to blast the annoying Politically Correct, the Bible Thumpers, the Grauniad Readers, and George Dubya with her mighty lightning bolt of sarcasm. Or she shouts at the radio.

‡‡ It can’t help but be more interesting than my written one, soon to be a major motion picture, called Angst of the Menopausal Mature Student, a cautionary tale about feeling sorry for oneself, complete with hot flushes and hysterics.

1 Eisner, Will. Comics & Sequential Art, Poorhouse Press, 1985.

2 There are numerous examples of comics attracting scholarly analysis:

—ImageTexT, http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/, a peer-reviewed, semi-annual, open access journal dedicated to the interdisciplinary study of comics and related media published by the English Department at the University of Florida with support from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

—Ellis, Allen. “Comic Art in Scholarly Writing, A Citation Guide”, Comics Art & Comics Area, Popular Culture Association http://www.comicsresearch.org/CAC/cite.html

— Dotinga, Randy. “Up, Up and Away, Indeed”, Wired, 07.24.06 http://www.wired.com/culture/lifestyle/news/2006/07/71442

3 Eisner, Will. A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories, Baronet Press, 1978.

4 Reid, Calvin. “Graphic Novel Market Hits $330 Million”, Publisher’s Weekly, 2/23/2007, http://www.publishersweekly.com/article/CA6419034.html

5 Smith, David Woodruff, “Phenomenology”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2005 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2005/entries/phenomenology/

6 Schumer, Arlen. “The Original Superman”, Comic Book Marketplace # 63, October 1998, http://theages.superman.ws/History/Version0.php

7 “Pauline Baynes Biography”, HarperCollins Children’s Authors & Illustrators. http://www.harpercollinschildrens.com/HarperChildrens/Kids/AuthorsAndIllustrators/ContributorDetail.aspx?CId=11788 and Tolkien Gateway http://tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Pauline_Baynes

8 Lewis, C. S. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Geoffrey Bles, 1950.

9 Book search results for N. M. Bodecker, Amazon.com http://www.amazon.com/s?ie=UTF8&search-type=ss&index=books&field-author=N.%20M.%20Bodecker&page=1

10 Cleary, Beverly. Beezus and Ramona, 1955.

11 Travers, P. L. Mary Poppins, Puffin Books, 1962.

12 John R. Neill, The Royal Illustrator of Oz and More http://www.johnrneill.net/

13 Tolkien, J. R. R., The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, (Appendices E and F, Tengwar (elvish writing) and Cirth (Elf/Dwarf runes), Ballantine Books, 1965.

14 Gaiman, Neil [w]; Keith, Sam [a]; Dringenberg, Mike [a]; Jones III, Malcom [a]; McKean, David [cover]. The Sandman – Preludes and Nocturnes, vol 1, Vertigo, 1988.

15 Gaimain, Neil. “FAQs: Advice to Authors: How do you write comics?”, Neil Gaiman’s Journal http://www.neilgaiman.com/faqs/advicefaq#q2

16 Lee, Stan [w] and Buscema, John [a]. How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, Simon & Schuster, 1978.

17 McCloud, Scott.

— Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, HarperPerennial, 1994.

— Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels, Harper, 2006.

18 Miller, Frank [w, a, i]; Jansen, Klaus [i]; Varley, Lynn [c]; Costanza, John [l]. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, DC Comics Inc., 1986.

19 Lee, So-Young [w, a]; Hayes, Sam Stormcrow [English adaptation]; McCaleb, Caren [retouch, lettering]. Model, vol 1, Tokyopop, 1999 [translation 2004].

20 Ohara, T. [translator]. “New Report from JETRO on the Manga Market in Germany”, Comipress Mon, 2006-09-04 01:01 http://www.comipress.com/article/2006/09/04/675

21 Haynes, Deborah. “Bible, Shakespeare get Japanese manga treatment”, Reuters Life! Mar 27, 2007 6:26 PM ISThttp://in.today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=entertainmentNews&storyID=2007-03-27T181213Z_01_NOOTR_RTRJONC_0_India-292415-1.xml

22 McCloud, Making Comics, ibid.

23 Edwards, Betty. Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, J. P Tarcher, Inc., Los Angeles, 1979.

24 McCloud, Understanding Comics, ibid.

25 Scott-Baron, Hayden, ibid.

26 Eisner, ibid.

27 Salisbury, Mark. Artists on Comic Art, Titan Books, 2000.

28 Salisbury, Mark. Writers on Comics Scriptwriting, Titan Books, 1999.

29 Brunetti, Ivan (Ed.). An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons & True Stories, Yale University Press, 2006.

30 Chocano, Carina. “Daniel Clowes”, Salon People, Dec 5 2000. http://archive.salon.com/people/bc/2000/12/05/clowes/index.html

31 Raeburn, Daniel K. Chris Ware, Lawrence King Publishing, 2004.

32 Sweatdrop Studios at Artist & Illustrator’s Exhibition at the Artists & Illustrator’s Exhibition at the Design Centre in Islington. http://www.sweatdrop.com/forum/calendar.php?do=getinfo&e=5&day=2005-7-21&c=1

33 Scott-Baron, Hayden. Digital Manga Techniques. Barron’s, 2005.

34 Interviewed Chris Francis, proprietor of Comics Plus, 17 Station Road, Aldershot, Hants GU11 1HT. See my reflective journal for interview notes and the Comic Expo in Bristol, 11-12 May 2007.